The Children of Central City

A New Orleans principal’s turbulent childhood

helps shape her students’ fragile futures

The drywall in their tiny shotgun was chipped and dirty and too thin to muffle her family’s fights. So, as a kid, Nicole Belt Boykins would bury her head in a book to keep the screams at bay.

She learned those books could be more than an escape from the violence around her. They would propel her to become the first member of her family to graduate from college, to earn a master’s degree in education and to find her place as a teacher, and now principal, at Lawrence D. Crocker College Prep.

Boykins, 32, recently completed her second year at Crocker’s helm. Located just outside Central City, it’s among a handful of New Orleans public schools experimenting with a relatively new approach to educating students – one that shuns zero-tolerance discipline that had been a hallmark of most post-Katrina charter school networks and, instead, focuses on addressing how trauma in a student’s life hinders his or her ability to learn.

Boykins is particular about hiring teachers who have overcome challenges in their lives. Research in New Orleans and elsewhere shows children regularly exposed to violence – in the home or in their communities – can suffer trauma similar to many soldiers returning from war. That trauma, says Boykins, and the turmoil it can cause in school, “will eat you alive and spit you back out.”

It’s also one of the reasons why Boykins was tapped to lead Crocker. Growing up in Central City and Hollygrove, she faced much of the same violence that scars her students. In them, her own life is reflected.

“No better person should run the school than Nicole,” said Amanda Aiken, Crocker’s former principal, now Orleans Parish School Board’s chief of external affairs. “She gets the trauma our kids suffer because she lived some of it.”

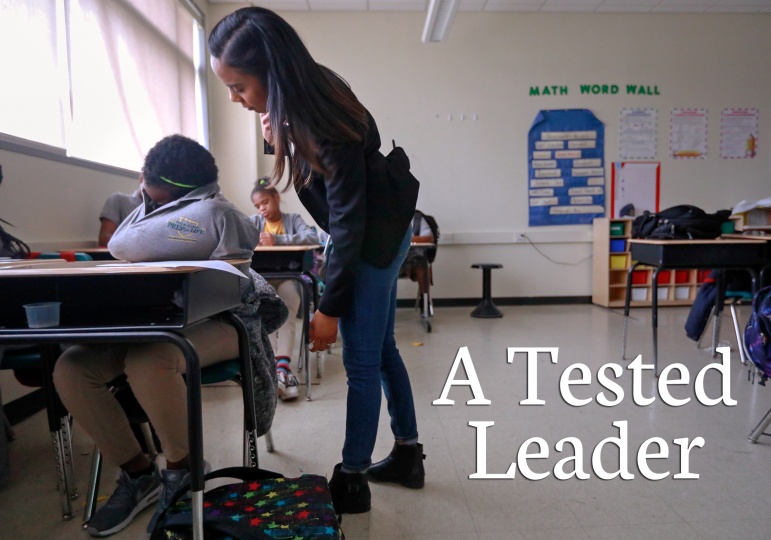

Crocker principal Nicole Boykins talks about how growing up in Central City and Hollygrove prepared her for her role as leader of a school at the forefront of addressing student trauma.

For Boykins, there was a palpable sense of community to those early years in Central City. Dozens of relatives lived alongside her on 3rd Street. She went to her great-uncle’s church on Derbigny Street every Sunday, even after her family moved to Hollygrove, and caught the start of the Zulu parade every year from her great-aunt’s porch at Jackson and South Claiborne.

Her father sold mattresses and her mother, a Japanese immigrant, worked at a leather shop on Claiborne near their home. On cold days, when her mom had to work early and Boykins and her older brother had a long wait for the bus to take them to school in the Melpomene projects, the owner of a nearby store would let them come inside to stay warm.

This is not to say she was shielded from Central City’s frequent violence. She recalls playing on the merry-go-round inside Taylor Park and hearing other kids talk about the woman whose bloody body was found nearby. Just recently, driving through the neighborhood, she recognized the spot where, nearly 25 years earlier, she saw a boy lying dead next to a bicycle in the middle of the street.

“He was in the street for a long time, because we stood out there for a long time,” she remembered during an interview in November. “It felt long to me. I kept thinking, when are they going to pick him up? They just leave you in the street for a long time.”

Hollygrove offered more of the same. From her porch on Eagle Street, she would watch neighborhood men – the same ones who watched out for her – scatter at the sight of an NOPD car speeding up the street, the slow ones picked off by the officers who jumped out and ran after them.

“All the people protecting me on this street, everybody’s handcuffed or everybody’s hands are on the car,” she remembered. “It’s crazy. The older you get the more you realize it’s very cliché to say you could end up dead or in jail. Literally, everybody I can think of from Eagle Street, they’re one of two places: dead or in jail.”

Home should have offered Boykins the respite she needed from the trauma she witnessed in her neighborhood.

It did not.

Like so many of Central City’s children, Boykins’ trauma began in the home. An analysis of New Orleans police data shows officers responded to more than 1,200 domestic-related calls in Central City last year, an average of three calls every day.

Boykins says her father is a “great man,” now. But, she admits, he wasn’t always that way. He drank, she says, and he lashed out at those around him. Her parents eventually divorced, but Boykins used to wonder why her mother didn’t leave earlier. Later, she says, she learned that her mom had been given a way out: A plane ticket to Japan, purchased for her mom by Boykins’ grandmother.

She remembers her mom’s explanation for why she didn’t take the ticket: “I could never leave you guys.”

While Boykins and her younger brother were mostly spared from their father’s direct ire, her older brother was not.

“Where there was a lot of leeway for me, and I didn’t push the line very much, there was not as much grace allowed to him,” Boykins says. “I could go in the kitchen and get orange juice and my dad would say, ‘Hey, go to bed.’ But if my brother snuck into the kitchen to get orange juice, it was game over.”

That difference in treatment extended beyond their father. The same neighbors who made sure Boykins was safe getting to school seemed to care little if her older brother skipped. In the classroom, where Boykins says her older brother’s academic abilities far exceeded her own, he found little support from teachers.

Her older brother’s behavior spiraled. At 14, he rode a bicycle through a hospital parking lot and snatched a purse from a woman. After getting caught bringing a gun to high school, he avoided jail time by leaving New Orleans for Boys Town, the Nebraska nonprofit that aims to help at-risk children. There, he earned his high school diploma. Afterward, he enrolled at McNeese State University in Lake Charles, but left in less than a year after their father stopped paying tuition.

“Now you’re back in the city, in the same neighborhood, around the same people who are doing the same thing,” Boykins says of her brother.

Orleans Parish court records show he was arrested four different times in 12 years, all on drug-related charges. In 2016, as Boykins began her first year as Crocker’s principal, her older brother began a 10-year prison sentence.

“It’s something that weighs heavily on me, when I think about grappling with being a principal and his realities look very different than mine,” she says.

There was a time when Boykins thought her brother’s life could have been different if he had chosen to deal with the trauma of their upbringing like she had: to retreat into her own mind, shutting off her emotions and willing herself not to cry.

“I remember thinking it all boils down to a choice,” she says. “He could have made this choice. And it was so many people coming back at me saying no, you don’t understand what it’s like for other people. People don’t process the same way.”

Boykins’ office is on the top floor at Crocker. It’s spacious, with a wrap-around desk and a big window overlooking the neighborhood below. Yet, she is not the type to hole up inside for long stretches at a time. Instead, she can be found walking the halls, smiling warmly and stopping to chat briefly with students she passes, or in a conference room near the first-floor main office, engaged in one of several student-parent meetings she’ll attend on any given day.

Though Boykins has been trained at Crocker to recognize how trauma affects students, she struggles to see the impact on her own life.

“I’m sure it comes out in some ways,” she says, leaning back in her office chair. “I think I’m a much colder person and desensitized to a lot of things, which is a gift and a curse.”

Being able to detach herself from emotion has allowed her a seat at the table, she notes. It gives her the ability to manage crisis, or to remain calm when faced with an angry parent.

“I can’t argue with people. Because I heard it so much as a child, that I vowed that I’m not going to argue with you,” she says. “We can disagree, but we’re going to disagree respectfully. So, the minute something gets beyond a conversational tone, I can no longer be engaged.”

But, she acknowledges, “there are things that I should be passionate about that I’m not very passionate about because I am desensitized to so many things.”

Since New Orleans’ traditional public school system was dismantled after Katrina, it has become less common to find educators who, like Boykins, grew up in the city. Given how close she once lived to Crocker, it’s not odd for her to encounter a parent she once knew from the neighborhood. Often, she says, they’ll grab her and hug her and tell her how proud they are that she “made it.”

“It’s funny because I don’t feel like I’ve made it,” she says. “I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing. But to everyone else, it’s a celebratory thing.”

Still, she admits to not knowing how she survived the neighborhood violence and poverty that consumed so many of her peers.

“When people speak about resilience, I understand it. I don’t know how I can function as an adult. To be honest,” she says, flashing a knowing smile, “I probably should get a therapist.”

- Previous Section

Stolen Focus - Next Section

A Family Team