Encounters with Digital "Jihadis"

When journalist Fadah Jassem was asked to contact "Jihadi John" and his companions on social media, she did not know what to expect.

A composite image of Abdel-Majed Abdel Bary (L) and journalist Fadah Jassem (R). Jassem contacted the Syrian-based foreign fighter for the first time in January 2014.

For me, 2015 was dominated by fear, a persistent fear caused by events in Syria. News headlines had given the terror a specific name: Jihadi John, the maniacal, machete-wielding man dressed in black who had become ISIS’s most infamous symbol up until his presumed death in an American-led air strike on Raqqah on November 12, 2015. It was my job to contact him and his companions, not out there in Syria, but in the borderless world of social media and from the apparent safety of an office in London.

As a collectivity, we as the media, it turned out, did not do such a good job in tracking him down. For months Jihadi John was said to be Abdel-Majed Abdel Bary, then he became Mohammed Emwazi. I’ll pick up on the story behind that misidentification later.

My intention here is not to focus on just one character in a cast of many, but to describe what it is like for a journalist to enter the world of “digital jihad” and to find myself in a landscape that is more deceptive and challenging to cover than the headlines might suggest.

The foreboding, fascination and fear surrounding Jihadi John as a news sensation began just as the summer of 2013 approached. I was working as a producer and assistant news editor in London, focusing on Syria, Iraq and the broader Middle East.

Journalists had begun picking up on the nascent social media activity of English-speaking men with British accents who seemed to be tweeting at us, ‘the west’, from inside Syria. Many were calling for jihad in the land of ‘Al Sham’ (Syria). As the year rumbled on, headlines grew bolder and stories of foreign fighters began to dominate the front pages of international news outlets.

But the reality is that young British men had been joining foreign battles in the Middle East and elsewhere for some time, even if the papers didn’t acknowledge it.

LIBYA – FIRST ENCOUNTERS

My first encounters in this digital space began at the height of the ‘Arab Spring’, just a few years before the onset of ISIS. I had interviewed a handful of young Brits who had joined the Libyan rebels in an effort to topple the regime there. They were quite pleased for me to follow their journeys of revolution and Jihad.

One of these men was a second-generation Libyan refugee from Belfast. He was friendly, passionate and approachable, and he shared the same goals as many others I had spoken to. First, they would fight for revolution and bring down Gaddafi; then, lay down arms and return home to normal lives in the UK. While some of these men shared conservative views on Islam, most didn't show any signs of extremism or radicalisation.

So when it came time to embark on a similar assignment in the summer of 2013 - to use social media to locate, contact and interview young British men who had left the ‘comforts’ of western society to fight alongside the Syrian rebels – I was fairly confident I could deliver. But I did not know then just how different it was going to be.

Before we go any further, let me clarify the concept of “Jihad.” The standard, simplified version of the term in Arabic, loosely describes an Islamic duty, which depending on the context can be translated as a ‘struggle’ or ‘the fight.’

In the West, jihad is generally understood as the ‘the holy war’ and mainly connotes the idea of military force. The Quran makes reference to jihad as both a military struggle on behalf of Islam, and an individual, spiritual struggle toward self-improvement, moral cleansing or intellectual development.

Terrorism, meanwhile, implies the use of threat, force or serious violence against anyone who stands in the way of some kind of ‘cause’. It is a different concept altogether. The merging of these two terms was hammered into the global collective consciousness during the Bush administration’s ‘War On Terror’.

During that time, the “terrorists” or “jihadis” in question were out there in far-off places like Afghanistan. Fifteen years on and the focus of the jihadist threat is being reported as homegrown and is represented by men from Europe’s shores.

The phenomenon provokes a number of sociologically-minded questions: why have so many young Western men and women been seduced by nihilistic and radicalised ideologies ostensibly based in Islam? Why are so many under the age of 30? And why the upsurge now?

Technology is one key factor. According to an interview in the Guardian with Jamie Bartlett, Director of think-tank Demos, the latest generation of Jihadist influencers are “technology literate, counter-culture, anti-establishment 20-something young men who have manifested themselves into the ‘jihadi cool’ generation.”

It is no surprise that the latest generation of radicalised fighters should adapt so smoothly to using social media.

Many of the first foreign fighters who arrived in Syria were extremely vocal on Twitter. They touted their purpose – toppling Assad – and promoted their divine calling for Jihad, believing it was their Islamic duty. They called their Western brothers to join them; and their use of social media platforms evolved quickly: the bolder the post, the better.

In no time, a vast array of Jihadist networks had established themselves online via Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and various blogging sites. Soon, the so-called ‘keyboard Jihadi’s’ or ‘disseminators’ became the most followed Jihadis. These ‘fan boys’ were not necessarily affiliated with any particular group, but spent their time cheering on foreign fighters and recruiting others. I followed these networks closely, and at the beginning, this image became one of the most influential.

It belonged to “Shami Witnesss,” one of the most persuasive voices for Western foreign fighters and “wannabe Jihadi’s”. To his 18,000 Twitter followers, Shami Witness was ruthless and persistent, hailing suicide bomber missions and actively encouraging people to leave their everyday lives for Jihad in Syria.

But Shami Witness lived a double life. Thanks to a formidable piece of investigative reporting by Channel 4 News, “the lion” was outted as a coward and hypocrite: an office executive with a comfortable job at an Indian conglomerate, who enjoyed Hawaiian-themed office parties and described his relationship status as ‘it’s complicated’ on Facebook.

It was easy to lose sight of the fact that the social media content flooding out of the region did not have a common origin – it was never one thing. There were different layers: adventurers in Libya, dedicated propagandists who had never seen any fighting and who were vicariously piggy-backing off the conflict in Libya, and increasingly the first signs of something that was different and better organised: ISIS.

SYRIA

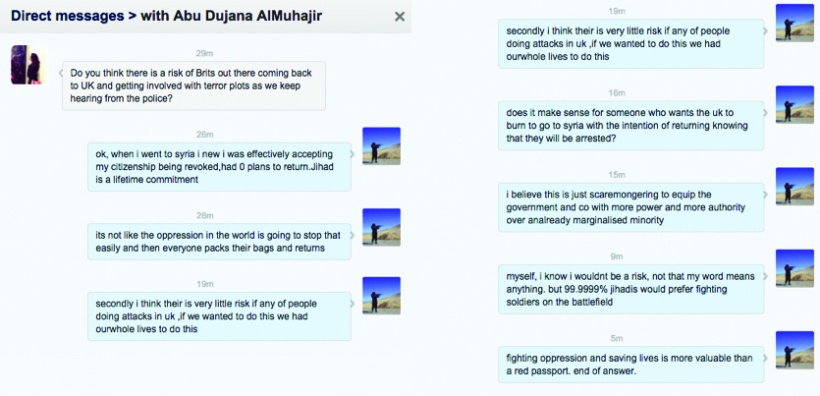

My first contact with a Syrian-based foreign fighter came in January 2014. His name was Abdel-Majed Abdel Bary, and he claimed to already be in Syria.

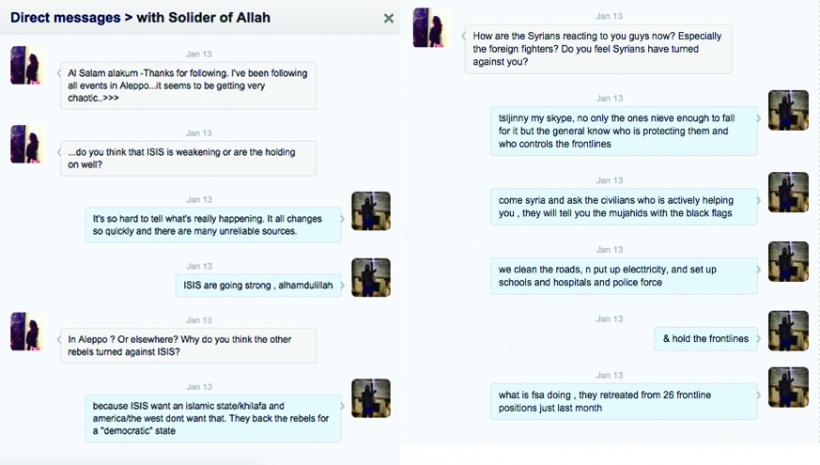

Our first exchange went like this:

At this point, many young Westerners in Syria had little knowledge of the political panic that was developing in the UK about British men fighting there. To me, Abdel-Majed seemed like a young Londoner who was quite eager to speak to anyone back home, perhaps to instill a degree of normalcy in his otherwise chaotic situation. He seemed relaxed and open to talking about his involvement with ISIS, along with his fundamental belief in establishing an Islamic State.

Over the next couple of months, I kept the conversations with Abdel-Majed alive by sending him articles published in the press about Western fighters. I did this for two reasons. First, to entice him into a Skype or phone interview with me, which proved to be almost impossible without the permission of his Amir, or direct leader.

And second, I had become interested in his thoughts on the subject of Jihad. As I am half-Syrian and half-Iraqi, it was easy for me to speak to other perspectives and to draw him into a conversation around what Syrians themselves might want for Syria. He engaged: my questions provoked a range of moral justifications for fighting the so-called ‘Kuffār’ or non-believers in Syria, whoever they may be.

But as the media and public’s interest in Western Jihadists grew, Abdel-Majed became more distant. His responses became progressively shorter until he stopped communicating with me altogether. I suspect that, perhaps not surprisingly, he may have become paranoid about speaking to a journalist he had never actually met.

JIHADI JOHN

Then on August 19, 2014 at around 10:00 pm a video emerged online featuring an English-speaking ISIS fighter with the captured American journalist, James Foley. In that video, ‘Jihadi John’ was born.

Not long after that, British newspapers dubbed Abdel-Majed ‘Jihadi John’. Why? I believe it was because he was an easy target, the lowest hanging fruit on the tree.

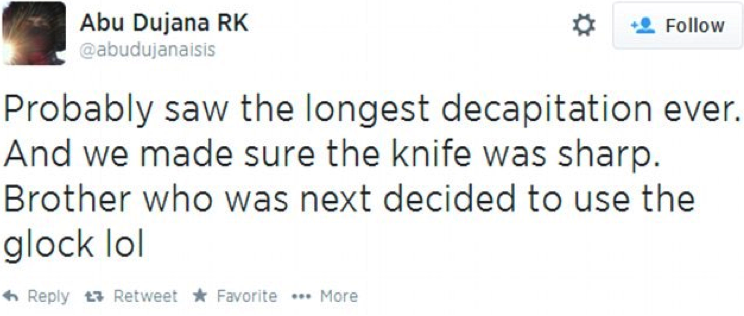

Abdel-Majed, also known as L’Jinny, had a few moderately successful rap videos online. His Youtube clips made it easier for journalists and ‘experts’ alike to analyse his voice, accent, and physical features against those of the masked, anonymous ‘Jihadi John’. Moreover, his well-documented social media presence from inside Syria included extreme and gruesome images, including severed heads.

In the end, Mohammed Emwazi, not Abdel-Majed, turned out to be the ‘Jihadi John’ whose image had terrorised the world.

At the time, I could not claim to know for certain, of course, whether or not Abdel-Majed was ‘Jihadi John’. However, our fragmented conversations led me to my own conclusions. Abdel-Majed was finding his way through the rapidly expanding and metamorphosing world of jihad as hijacked by ISIS. I believe he was a fervent young man, looking for a cause. That cause, unfortunately, became ISIS and not the initial idea of jihad that he had hoped to join. The embers of Abdel-Majed’s extremism had first began to glow in London, where they were stoked by a working class, anti-establishment locus; in Syria, they flared into something far more deadly.

Abdel-Majed found it hard to respond to my arguments concerning humanity and divinity: I assume that was because he had his own demons and moral objections to contend with. Like many others, he considered returning home, but ultimately felt trapped.

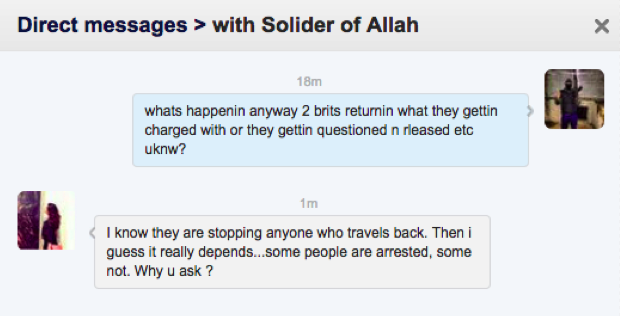

Here is the last message he sent to me:

Later on, I found confirmation that he had become disillusioned with life in Syria: he reportedly disguised himself as a refugee in Europe, and is now said to be on the run, hunted from all sides, by both the British security services and his former ISIS compadres.

One might well ask whether he is a threat now. That is both possible and probable. Nevertheless, I do wonder what might have happened if he hadn’t been so ruthlessly targeted by the tabloids and been accused of being ‘Jihadi John’, despite the lack of any real evidence. This is speculation on my part, but perhaps there would have been other options for him to find a way back to a more normal life.

Reyaad Khan is a different case. He was one of many young men and women who adopted ISIS’s dogma before leaving the UK. I made contact with Khan [when?], but did not succeed in engaging him in any consistent manner. He was clearly uninterested in spending time talking to journalists. He did, occasionally, respond to a question or two, but only to trick me or another journalist into thinking he might be willing to talk.

Khan’s commitment to ISIS and its version of Jihad appeared whole-hearted. He relished the non-stop media frenzy in his tweets, mocking Western governments, Western beliefs and the idea of democracy. On July 8, 2015, he tweeted:

Months later, it was reported that Khan had been killed in a precision RAF drone strike back on August 21, 2015.

Abdel-Majed Abdel Bary and Reyaad Khan started out from different places. To use categories coined by Shiraz Maher of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, the former might be described as the ‘adventure seeker’, the latter as the ‘real nasty guy’. Despite different aspirations, they both ended up in the same place: using social media as a vehicle for violence.

Maher also contends that a third type of new age foreign fighter exists: the ‘idealistic or humanitarian jihadist’. These are people who are initially motivated by the human suffering endured in predominately Muslim countries, and who wish to help.

I encountered a couple of young men who fit into this typology, most of whom quickly became ‘martyrs’ for Jihad. One was Mahdi Hassan, a 19-year-old who traveled to Syria with four others, all friends from Portsmouth, a coastal town, South of London.

They seemed to be motivated by an Islamic duty to alleviate the suffering of others of the same faith and determined to begin ‘pure’ Islamic lives under ISIS. In this exchange, Mahdi Hassan expresses devotion to this way of life, echoing what many others also told me:

Over time, these young men became hardened by their surroundings and loyal to the idea of imposing an extreme idea of Islam, rather than saving the ‘innocents of war’. The focus became to destroy enemies of Allah, whoever they may be.

It was at this point that I became less and less motivated to engage with them. As someone with family in both Syria and Iraq, it became progressively harder for me to exhibit professional neutrality when confronted by their dogma. The gap between “us” and “them” also began to widen across societies in the UK and the Middle East alike.

THE FOCUS SHIFTS TO THE FAMILIES

Approximately a year after our first contact, I had lost touch with with Abdel-Majed, as with most of the others. The media’s interest moved towards their families: who were they? How had they let their children leave to fight in Syria or Iraq? Should they be held accountable for their children’s actions?

Every so often the true identities of these young men came to light. Sometimes a journalist or terrorism expert found a way to expose them; at other times online Jihadists broke the news on social media by announcing the ‘martyrdom’ of their fellow brothers in arms. This in turn led journalists to their families, friends and relatives, and, at least partially, to these men’s stories. But now the families had to pay an additional price on top of their bereavement: harassment by sections of the media and a public shaming for having “allowed” their “loved ones” to become extremists.

The trajectories of these young men and women are difficult to track. Some who joined the caliphate in Syria or Iraq and later became disillusioned may have slipped back into more ordinary lives. Others are now in an even better position to use the new weapon of social media to disseminate their propaganda. What is to stop the latest generation of wannabe Jihadists from being influenced by extremist doctrine? It is within easy reach: it is at their fingertips.

I believe it is our duty as journalists to keep lines of communication open with these young men and women, wherever and whenever possible, despite the challenges.

Looking back, I can see how important my curiosity was in driving me towards these encounters. I was searching for explanations and even, perhaps, solutions to the threat these young men embody. Given the danger they posed, social media allowed me to get as close as I could. It created the space for me to ‘get to know’ people who oppose everything I believe in but who yet have so much in common with me because we come from the same place. Looking back at those fragments of conversation, many of these young men didn't seem menacing or even threatening to me.

I don't believe that all of them went to Syria with a goal of beheading innocent people, or necessarily even hurting them. What I am certain of, however, is that doctrines that promote inhumane acts of terror, whilst cloaking themselves in the auspices of righteousness, have an inherent capacity to corrupt; they can indoctrinate and transform anyone who comes under their misguided philosophies.

In this vortex of terror, many of its casualties are and will continue to be young and impressionable men and women. War breeds terror, war magnifies hate, and we as a society don’t have the luxury to ignore either.

*Note: I should make it clear that the nature of my journalistic work as a broadcast news producer required me to focus on obtaining visual or audio format interviews. So up until now I have not shared any of these conversations publicly. The people I spoke with all knew who I worked for, and that I was a journalist. I did not pretend to be anyone other than myself.